Jason Boyd Kinsella’s poetic tribute to Langston Hughes has been installed in central London, just opposite Tate Britain.

Kinsella is widely acclaimed for his painterly style that approaches subjects from a multitude of geometric perspectives, and his new sculpture Langston offers a psychological portrait of the poet Langston Hughes.

Beyond poetry, Hughes was a prolific novelist and activist, and a major figure in the Harlem Renaissance. Upon discovery of Hughes’ work as a student of poetry, Kinsella was gripped by its potency, recalling: “Many poets concerned themselves with love, beauty and nature… but Hughes had an ability to use words in a way that can transport you to another place and time. There’s a powerful visuality in his work.”

The bronze sculpture Langston pays homage to Hughes, casting the inner world of the poet’s mind in a protean mix of geometric shapes, testament to the strength and versatility of the poet’s written works.

Kinsella conceived the piece first through preliminary sketches and studies on paper, before enhancing them through 3D software and casting the final design in bronze. Public audiences will be left to appreciate the large-scale portrait that is both conceptually enticing and technically accomplished.

The display, part of the Borough of Westminster’s City of Sculpture programme, is installed on London’s Riverside Walk Gardens in Millbank in a privileged position between Tate Britain and the Thames, alongside Henry Moore’s Locking Piece which was gifted to Tate in 1968. This initiative was in cooperation with Unit London.

“An investigation of simplifying features into strange beautiful shapes, and an exploration of the interiority and exteriority are absolutely present.”

– Melissa Smith, Curator, Art Gallery of Ontario

GHOST IN THE MACHINE

PERROTIN SEOUL

August 30 to October 19, 2024

Perrotin Seoul is pleased to present Ghost in the Machine, a solo exhibition by Canadian artist Jason Boyd Kinsella, based in Oslo. At the core of Kinsella's art is the representation of the human mind and psychology. Drawing on subjective perspectives and the Myers–Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), the artist explores the nature of the human psyche by breaking down traits and personalities into geometric units, defining individuality through various shapes, colors, and sizes.

The exhibition's title, "Ghosts in the Machine," is a phrase coined by British philosopher Gilbert Ryle to describe his critique of mind-body dualism, a theory advocated by French philosopher René Descartes. This theory posits that the body and mind are fundamentally distinct substances and that they can exist independently of each other. Ryle criticized this distinction for failing to account for the interaction between body and mind. Kinsella's paintings focus on isolating and revealing the unseen self (mind) as an entity separate from physical space (body or material existence). While traditional Western portraiture has aimed to represent the body through external depictions, Kinsella's works are psychological portraits emphasizing the interconnectedness of the mind and body while still distinguishing between them. As the artist puts it, this approach offers "a new way of representing the self today."

The clean surface of his paintings recalls classical art. Kinsella's paintings incorporate various elements of classical portraiture, such as finely tuned sfumato, compositions that capture the upper half of the human body, and linear perspective, but he also actively borrows from technologies such as digital rendering. Ultimately, his figures, created by blending analog and digital methods, are, like all good portraits, representative of contemporaries and a mirror to the complex and contradictory inner lives of people.

There is a dynamic economy in Jason Boyd Kinsella’s paintings of cubic portraits. Reduction generates a kinetic potential for the sitter whose semblance both cherishes and complicates two pillars of portraiture, the emotional complexity and a visceral likeness. The Oslo-based Canadian traverses art’s innate essence to capture the human physicality through various penchants across time: Pre-historic simplicity of the stick figure, Renaissance era’s grasp of the facial expression for transcendence, and the distorted contemporary abstraction. He builds his case on an interplay between the malleable motifs of existence—bodily as well as cerebral—and a minimized configuration of imperative gestures, particularly the line and the circle.

Stripped to the essential, the oil paintings and sculptures in Ghost in the Machine incorporate the canonized into an openness for pliability. The exchange is indeed codependent. Imagination is unlocked through the aperture of forms that defy a direct representation. A tube could be a neck or a limb—or neither. Two discs resemble eyes but they also exist simply as circular shapes. This vastness of possibilities animates a portrait, broadening the vocabulary of an emotive language within geometry. “Today, there are so many ways people can escape from their true selves,” says Kinsella. “It becomes more and more confusing and difficult to ascertain a true likeness of somebody.” The intricate process of association ushers an intuitive connection between the subject and the viewer—the assemblage of geometric forms suggests a rather felt idea of a portrait as opposed to a deliberate illustration.

The show's only video work, Self-Portrait (2024), turns Kinsella's painterly gaze towards himself. Humorous and self-satirizing, the two-and-half minutes long film lifts the curtain to the artist's creative operations and life, carrying the camera into his studio and personal space. Kinsella paints, cleans, plays guitar, and draws at a lingering Scandinavian pace while his mannerism suggests contemplation and search. The emotions however are on the viewer to predict: the artist's face remains swapped with a portrait a lá Kinsella through the video's finale. Colorful pyramids, tubes, and discs fill in for his facial features on the surface, as well as constructing, deep down, his own emotional panorama in abstraction.

— Osman Can Yerebakan

EMOTIONAL MOONSCAPES

PERROTIN NYC – Feb 24 to April 6, 2024

Perrotin is pleased to present Oslo-based artist Jason Boyd Kinsella's inaugural U.S. exhibition, EMOTIONAL MOONSCAPES. On view through April 6th, the exhibition consists of two immersive environments on the gallery's second and third floors, introducing the artist’s foray into combining various mediums, such as painting, sculpture, and video.

Jason Boyd Kinsella is a portraitist not much interested in what people look like. His have no people in them at all, in fact, or at least not the way we’re accustomed to seeing ourselves. Kinsella understands portraits can do one of two things: they can capture the likeness of their subject—the contours of a face, their jowliness, their creases and crags; or they can distill something truer, where likeness is secondary to affect. This is the difference between what someone looks like to others, and what they look like to themselves. Good portraits are always psychological portraits.

We are all utterly convinced that we engage with the world in deeply specific ways legible only to us, our perceptions and quirks and mechanisms irreducible. But the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator prescribes only 16 possible personalities, 16 ways of being in the world (introvert/extrovert; carefree/worried, and so on). Nevermind that these binaries are mostly rejected as pseudoscience. Kinsella, having successfully jettisoned traditional facial structures, finds new purchase for the typology, an abiding fascination ignited by a childhood gift of a Briggs book. He maps the Indicator’s precepts onto intricate, teetering assemblies of geometric forms — building blocks, literally, of psychological attributes.

While the results have the clean, highly finished surface of Googie architecture or alien tesserae, their spiritual forebears are in fact the Old Masters. The classicism is all there: the 3/4 quarter pose, the finely-tuned sfumato, the fixation on linear perspective — like Rogier van der Weyden’s Portrait of a Lady stripped of flesh, reduced back down to rhomboids. Though they’re piles of blocks, they retain humanness. They emote, are inquisitive, proud, defiant taciturn. They can be vulnerable or steely, cool or sheepish. All of this is accomplished without eyebrows.

Kinsella doesn’t make self-portraits, except every picture he makes is a kind of self-portrait, his presence wrapped up in his pictures, implicated in it, “an intangible familiarity,” he calls it, a feeling that hangs between the shapes. His shapes, held together by a thin gravity, have a precarity, the feeling that things could easily come undone. This makes them, in the end, about life — stubbornness in the face of impermanence. On the second floor — the emotional moonscape of the show’s name — sits its largest work. Connection (2024) depicts two figures that yearn to connect but never do, isolated in a yawning, serene expanse. Something keeps them apart, but they knock against it anyway.

— Max Lakin

“I gravitate to geometric blocks because they are the simplest and most honest forms of expression that enable me to see a person without distractions. There’s nowhere to hide.”

— Jason Boyd Kinsella

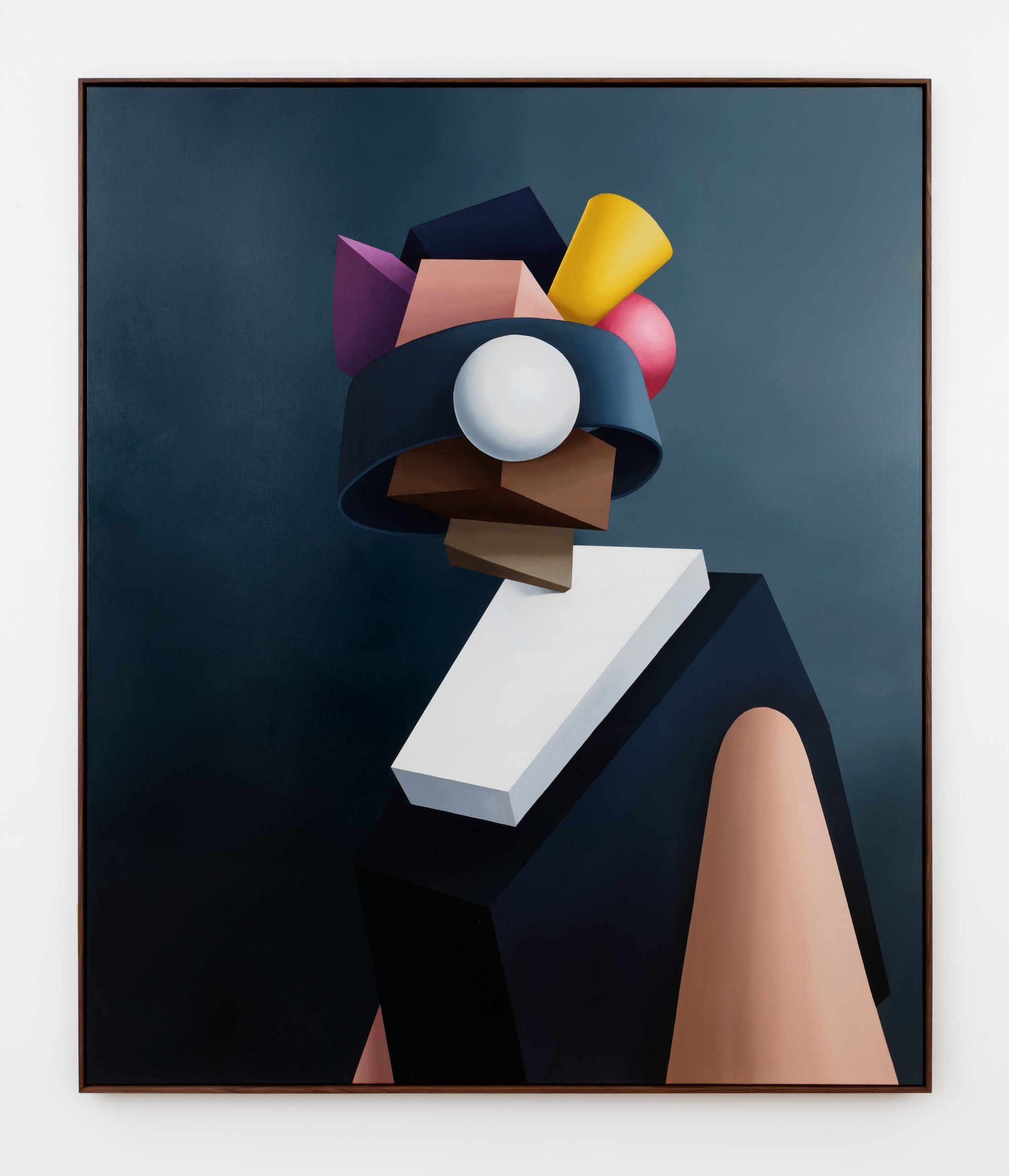

ANATOMY OF THE RADIANT MIND

UNIT LONDON – Oct 3 to Nov 4, 2023

Canadian-born artist Jason Boyd Kinsella returns to London to present his second solo exhibition at the gallery. This exhibition contains a bold and exciting new body of paintings and sculptural works which represent an entire year of tireless preparation. The month-long presentation will coincide with Frieze London.

Jason Boyd Kinsella’s newest solo exhibition with Unit London presents a series of abstract portraits and sculptures that aim to visualise an ‘unseen world’. Through what the artist identifies as ‘fleshless portraiture’, Anatomy of the Radiant Mind strips away layer after layer to reveal the unconscious essence of each subject.

Psychological portraiture remains at the core of Kinsella’s artistic practice, which uses colourful geometric forms to represent the intricacies of individual psychology. Each portrait comprises many interlocking parts that represent distinctive personality traits. More complex in form than previous bodies of work, Anatomy of the Radiant Mind demonstrates the evolution of the artist’s practice, striving to bring clarity to the intangible world of the subconscious self.

In refining his singular visual language, Kinsella includes a centrepiece of a full body figure, introducing a new narrative quality to this body of work. Individuals are no longer limited to three-quarter length portraits but expand across the entire canvas, pushing the parameters of this type of psychological portraiture. Moreover, Kinsella presents three-dimensional artworks alongside his canvas works. Juxtaposing sculpture and painting, the artist aims to discover whether individuals can be truly grasped in two dimensions. Speaking to the all too frequent conundrum of our contemporary age, Kinsella explores what is genuine and what is not and asks whether we can truthfully represent another person.

First and foremost, Anatomy of the Radiant Mind explores an ‘unseen world’ that is closely tied to the unconscious. Inspired by the deep universe of dreams and imagination, these portraits tap into abstract notions of selfhood. Kinsella’s portraits are less concerned with external appearances, choosing instead to reflect what is hidden underneath. In our contemporary age, it becomes increasingly tempting to lose ourselves in ideas of physical appearance and self-image. We are attuned to seeing ourselves through the lens of how others see us, particularly in the context of social media. As a result, we have become adept at transforming our outward identities to suit specific circumstances both online and offline. While Kinsella’s visual language leverages this ability to adapt to new ways of seeing ourselves and others, it hones in on the true nature of individuals, paring subjects back to their essential form.

These portraits therefore make use of a hybrid visual language that lives both in the past and the present. The modern idea of the malleable digital self exists within these artworks, but at the same time, these paintings engage with a deeply rooted history of portraiture. These artworks therefore sit on the boundary between pre- and post-internet painting, seemingly bridging a divide by offering a new type of portraiture that aspires to simple truth in an over-stimulating digital world. Reflecting these ideas, Anatomy of the Radiant Mind focuses on materiality. When in previous bodies of work Kinsella has concentrated on digital assets, here he centres on the practical tools of brushes and paint, celebrating the potential of oil as a medium.

With Anatomy of the Radiant Mind, Kinsella challenges the limits of his own visual language, venturing further technically to mine the depths of the unconscious mind. In an artistic process that borders on stream of consciousness, Kinsella creates intuitive portraits that blur boundaries between past and present, digital and analogue, two and three dimensions. Pulling on this visual thread, Kinsella strives to eliminate the distance between his artistic vision and what appears on the canvas, ultimately aiming to bring viewer and artwork closer together.

MENTALVERSE

PERROTIN – Nov 25 to Dec 30

On the occasion of the debut of Perrotin in Dubai, the gallery is partnering with ICD Brookfield Place to organize the first exhibitions of Jason Boyd Kinsella in the Emirates. The artist presents a new body of sculptures and paintings through exclusive scenography. His work will be presented in parallel to an exhibition by Takashi Murakami.

“Deftly classical yet undeniably contemporary, it is as if incompatible worlds collide in the heads of Jason Boyd Kinsella. ”

— Carlo McCormick

In portraiture, virtuosity has long been measured by verisimilitude. How one must wonder then does this quotient of likeness hold its esteem in a metaverse where the production and distribution of visual culture depends so much on likes, and where the broadest proliferation of portraits exists in an incessant stream of selfies- so many of them composed with the most posed calculations and referential iconographies of old masters and mediated through myriad filters to make us look better than our appearance? Jason Boyd Kinsella, an analog savant and maestro painter, steps into the digital paradigm with an intrepid affection for the mutability of self in the metamorphic fictions of appropriations and avatars, reconsiders this chasm between fact and fiction as a bridge rather than a breach. By foregoing the mandate of the easily recognizable in lieu of a more evasive but no less determinate psychological recognition, Kinsella shifts the conversation from the specificity of people to the commonality of humanity. We are likely not familiar with his subjects in a personal way, but through his paintings and sculptures we come to know them as personalities.

View of Jason Boyd Kinsella's exhibition 'Mentalverse' at Perrotin Dubai, ICD BROOKFIELD PLACE - DIFC DUBAI 2022. Photo: Altamash Urooj. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin

Obviating the anatomical characteristics that serve caricaturist and facial recognition technology so well, and eschewing the consumer habits that come to define who we are with the precision of an algorithm, Jason Boyd Kinsella is at once reductive and expository. Details are incidental, even gratuitous, to Kinsella who builds his personae as a kind of elemental architecture, an edifice whose structure is both emphatically geometric and discretely conceived as a psychological framework. The ever-ornery James McNeill Whistler (himself a brilliant portraitist) acknowledged the talents of another portrait painter in his collected writings, The Gentle Art of Making Enemies, while dismissing him for working in so “mercantile” a medium. Though Jason’s assembled visages are as seductive as any, he has little inclination for the flattery by which the visual impersonation of another posits an idealized sense of immortality. His is not an art of particulars but an investigation of archetypes. Whereas most artists mine the emotional or physiognomic idiosyncrasies of their subjects to limn some empathic connection with the viewer, Kinsella is most concerned with articulating the primary archetypes of personality that make each of us, for all our differences, far more universal than unique.

Photography by Andris Søndrol Visdal

A lifelong artist who only committed to painting full-time after an extended and successful tenure in advertising, Kinsella’s near-immediate phenomenal success- of a sort typically enjoyed by the proverbial hot young artists- is as much about his uncanny ability to hit the zeitgeist with a timelessly classicist mode of representation that addresses the slippery slope of identity, authenticity and actuality at a time when these very terms are simultaneously reified by and diverted within the spectacle of social media, as it is about de-cluttering our gaze away from this field of perpetual distraction onto, and into, contemplative forms. If you get the sense that he spent much of his childhood immersed in the masters, that is true as is how his wasted youth in the vibrant Punk and Skate Cultures now invests his art with a youthful questioning and unorthodox mode of navigation. He allows, like the best of us, a generous and fluid historical mash-up, but significantly, one that converges organic thinking and digital experience. Stylistically proximate to Cubism in its emphasis on primary geometric forms such as cubes, spheres and cones, Kinsella’s abiding fascination with shapes in space (playful in a way akin to a child conjuring the world through building blocks) could not be more different that the concerns of Analytical and Synthetic Cubism which obliterated the rules of Renaissance Perspective in favor of a flattened space in which the multiple perspectives of our bifocal sight dynamically shift compositional absolutes. Rather we see an artist here who employs the full representational toolbox of light, shadow, tonality and depth that precedes Modernism’s assault on the picture plane, and is in fact now foundational to the coding through which computer-assisted art is generated.

Photography by Andris Søndrol Visdal

Deftly classical yet undeniably contemporary, it is as if incompatible worlds collide in the heads of Jason Boyd Kinsella. This oppositional synthesis, time-tripping like a tune so fresh and formidable that it sounds profoundly familiar from the first listening, is somehow even more lively in Kinsella’s sculptures, exhibited here for the first time. Of all sculptural genres, few have seemed quite so arcane to contemporary expression than that of the bust, yet Kinsella, flipping back and forth through processes ranging from hand drawing, digital rendering, maquette building and computer animation, explodes the form with subversive whimsy and bravura balance that has all the figurative legibility of a Jacques Lipchitz and the shiny perfect guise of a digital simulation. Paired together, the paintings with the sculptures, we are able to better ascertain the aesthetic attractions undergirding Kinsella’s rampant hybridity, in particular a deep seeded minimalist impulse, a kind of less is more rigor that imbues his art with a considered craft, patience and discipline, and an acute eye to the precepts of design that are sadly overlooked by many contemporary artists. Stripped down to the basics of necessity, Kinsella’s reductive terms assert their presence without embellishment, activating his compressed yet open-ended compositions in such a way that we marvel at the immense sum of their modest parts, articulated in eye-candy primary colors where no single part takes precedence yet all dance together in radically choreographed complexity of interactions.

—

Carlo McCormick

Read an article about the exhibition here:

THE IMPERMANENT STATE OF BEING

PERROTIN - March 26 to May 21, 2022

Perrotin is pleased to present Jason Boyd Kinsella’s first solo show in France. This exhibition debuts a new series of paintings, highlighting the artist’s continued exploration of the ever-changing state of being.

“My visual language telegraphs this impermanence by illustrating our existence as a delicate assemblage of shapes unbound by flesh.”

— Jason Boyd Kinsella

Jason Boyd Kinsella’s paintings have all the clean-surfaced, tight-framed hallmarks of an old master painting, the stacked geometry of cubism, the illogical, dreamlike qualities of surrealism, yet jut out from their canvases like nothing else.

‘My visual language telegraphs this impermanence by illustrating our existence as a delicate assemblage of shapes unbound by flesh,’ he says. ‘Each colourful building block is open to new combinations of elements – like some visual alchemy.’

Kinsella – born in Toronto and now based between Oslo and Los Angeles – took up painting again in 2019 following a 30-year hiatus. ‘The Impermanent State Of Being’ at Perrotin Matignon 8, Paris, marks the artist’s first show in France, and presents

a series of new works that examine perpetual fluctuations in states of being. Though the parallels with painting history are clear (not least in their immaculate mastery of perspective), Kinsella’s portraits are resolutely contemporary, both in theory and practice.

Read the entire review in Wallpaper* Magazine – Click Here

Impermanence, Digital/Film, Jason Boyd Kinsella, 2022

FRAGMENTS

UNIT LONDON – April 27 to May 24, 2021

Unit London is pleased to present Jason Boyd Kinsella’s first solo show in London. This exhibition debuts a new series of paintings, highlighting the artist’s exploration of the building blocks of our psychology.

“Each colorful building block is open to new combinations of elements – like some visual alchemy.”

— Jason Boyd Kinsella

A quick glance at the works by Jason Boyd Kinsella deciphers a familiar form of a human figure, which then instantly dismantles into an amalgamation of flawless, colorful, otherworldly shapes that construct the initial mirage. These geometric fragments, which the Canadian artist uses as building blocks to represent the complexity of the human condition, are simultaneously evoking our reliance on digital technology and its influence on our psyche. And it’s such focused interest in the human psyche that resulted in his work being labeled as hyper-contemporary psychological portraiture, as it allows him to create an endless amount of assemblages which then symbolize the endless combinations of character traits we’re all built from. With the purposely obvious use of technology and 3D rendering software in his creative process, the reference to interconnectivity between the natural and the artificial becomes even more relevant and somewhat personified.

“I love the way Kinsella uses psychological tools like the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator to dissect human archetypes and then applies his unique visual language to portraits.”

— Alan Lau

Alan, Digital/Film/NFT, Jason Boyd Kinsella, 2022

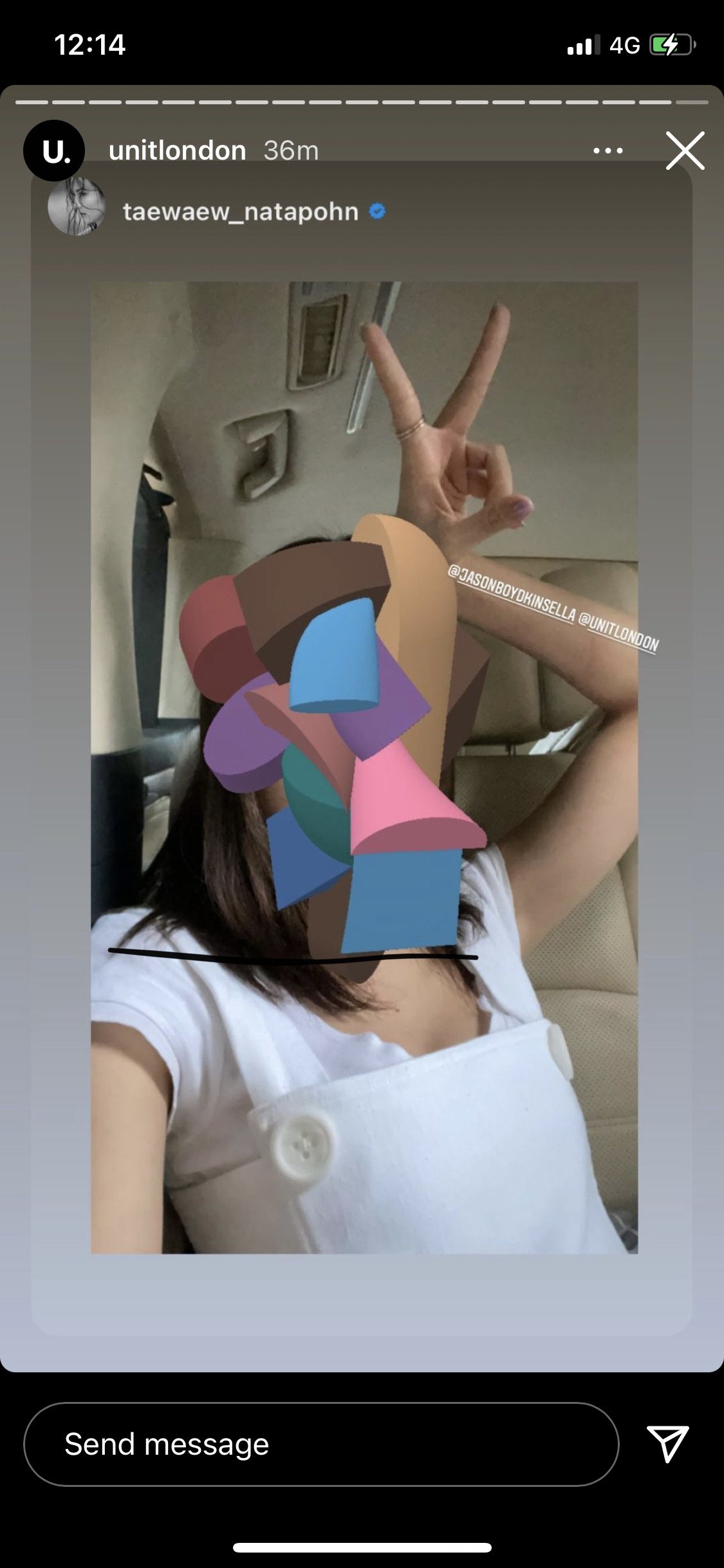

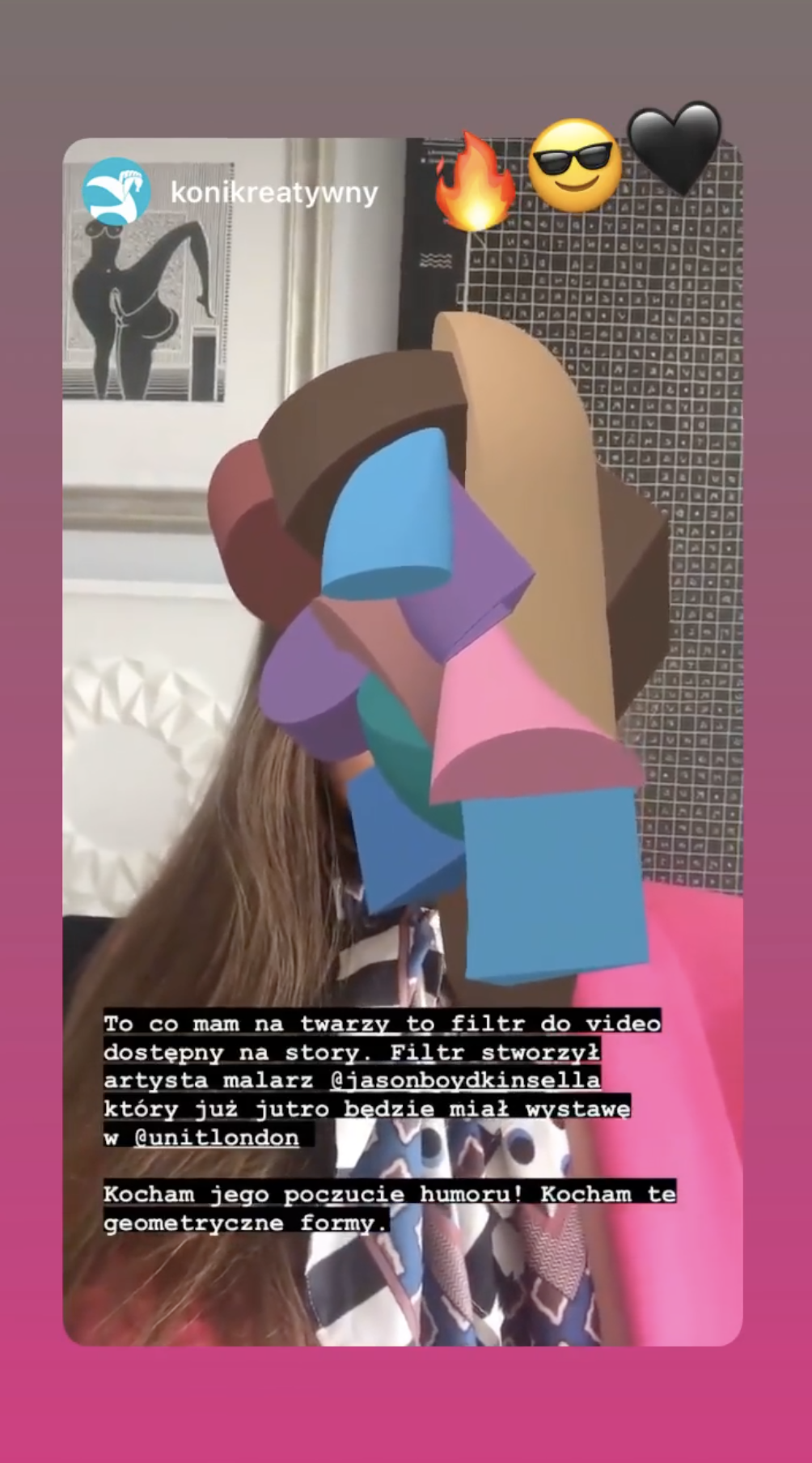

In connection with the Fragments exhibition, I created an Instagram facial tracking filter that enabled people to instantly transform themselves into one of my portraits.